Introduction

In recent years, a growing concern has emerged within the realm of eye health and vision care—myopia, commonly known as nearsightedness, has been on the rise at an alarming rate. Once considered a relatively common refractive error, myopia has now reached epidemic proportions, particularly among younger populations. This blog aims to shed light on the myopia epidemic, its causes, consequences, and potential strategies for prevention and management, drawing insights from credible sources and scientific research.

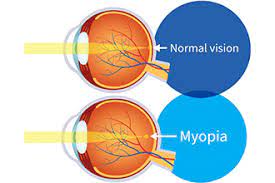

Understanding Myopia

Myopia is a visual condition where distant objects appear blurry, while close-up objects are clear. It occurs when the eyeball is too long or the cornea has excessive curvature, causing light to focus in front of the retina rather than directly on it. The prevalence of myopia has skyrocketed in recent years, affecting both children and adults across the globe. A study conducted by the Brien Holden Vision Institute projected that nearly half of the world’s population, approximately 5 billion people, would be myopic by the year 2050 if the trend continues unabated.

Causes and Contributing Factors

Numerous factors have been linked to the myopia epidemic. Excessive near work, such as reading, writing, and prolonged screen time, is often considered a significant contributor. The prevalence of digital devices in today’s society has led to a substantial increase in near-focused activities, especially among younger individuals. This phenomenon, combined with reduced outdoor time and exposure to natural sunlight, has been associated with an increased risk of developing myopia.

Scientific Studies and Research

Several scientific studies have offered insights into the myopia epidemic and its potential causes. A comprehensive meta-analysis published in JAMA Ophthalmology found that increased outdoor time and engagement in outdoor activities during childhood can significantly reduce the risk of myopia development. The “Singapore Cohort Study Of The Risk Factors For Myopia” demonstrated that higher levels of near work and limited outdoor time are strong predictors of myopia progression.

Consequences of Myopia

The impact of myopia extends beyond just blurry vision. High myopia, characterized by a severe degree of nearsightedness, can lead to a heightened risk of vision-threatening conditions such as retinal detachment, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. These conditions can severely impair visual acuity and overall quality of life. Additionally, the economic burden of myopia, including the cost of corrective lenses and medical treatments, is substantial and places a strain on healthcare systems globally.

Preventive Measures and Management Strategies

Recognizing the urgency of the myopia epidemic, various preventive measures and management strategies have been proposed. Encouraging outdoor activities and limiting screen time for children have shown promising results in reducing the risk of myopia. Additionally, the use of specially designed contact lenses or eyeglasses, known as orthokeratology or multifocal lenses, has been explored as potential tools to slow down myopia progression in children.

Conclusion

The myopia epidemic is a complex and pressing issue that demands attention from the medical community, policymakers, parents, and individuals alike. Scientific research highlights the correlation between near work, outdoor time, and myopia, underscoring the need for a holistic approach to eye health and visual well-being. By understanding the causes, consequences, and potential solutions, we can collectively work towards reversing the myopia epidemic and safeguarding the vision of future generations.

Sources:

Holden, B. A., Fricke, T. R., Wilson, D. A., Jong, M., Naidoo, K. S., Sankaridurg, P., … Resnikoff, S. (2016). Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology, 123(5), 1036–1042.

French, A. N., Morgan, I. G., Mitchell, P., & Rose, K. A. (2013). Risk factors for incident myopia in Australian schoolchildren: the Sydney adolescent vascular and eye study. Ophthalmology, 120(10), 2100–2108.

Wu, P. C., Huang, H. M., Yu, H. J., Fang, P. C., Chen, C. T., & Chen, C. Y. (2013). Epidemiology of Myopia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology (Philadelphia, Pa.), 2(6), 405–413.

Xiong, S., Sankaridurg, P., Naduvilath, T., Zang, J., Zou, H., Zhu, J., … He, M. (2017). Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmologica, 95(6), 551–566.

Saw, S.-M., Tong, L., Chua, W.-H., Chia, K.-S., Koh, D., Tan, D. T. H., & Katz, J. (2008). Incidence and Progression of Myopia in Singaporean School Children. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 49(9), 3846–3852.

Flitcroft, D. I. (2012). The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 31(6), 622–660.

Walline, J. J., Lindsley, K., Vedula, S. S., Cotter, S. A., Mutti, D. O., Twelker, J. D., & The Vision CRC Group. (2011). Interventions to slow progression of myopia in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2011(12), CD004916.